‘The Caldecott Notion’: Sam speaks on last week’s picture book awards announced by the ALA

The Student of Prague – 1926, Henrik Galeen

by Allan Fish

(Germany 1926 95m) DVD1

Aka. Der Student von Prag

He gambled with his soul and lost

p Harry R.Sokal d Henrik Galeen w Henrik Galeen, Hanns Heinz Ewart story Edgar Allan Poe ph Gunther Krampf, Erich Nitzchmann art Hermann Warm

Conrad Veidt (Balduin), Werner Krauss (Scapinelli), Fritz Alberti (Graf Schwarzenberg), Elizza Porta (Liduschka), Agnes Esterhazy (Margit), Ferdinand von Alten (Baron Waldis Schwarzenberg),

Take a crash course in German Expressionism in the 21st century and a great injustice will be perpetrated borne out of ignorance. We know Murnau, Lang, Pabst, of Robert Wiene for Caligari (if little else) and Paul Wegener for and as Der Golem. Yet it’s a summary guilty of numerous oversights. Such avant garde pioneers as Hans Richter and Walter Ruttmann, Kammerspiel founder Lupu Pick, Paul Leni, E.A.Dupont, Joe May and Hanns Schwarz all merit a mention. As do the likes of Hermann Warm, Karl Freund and Fritz Arno Wagner. Not to mention the man who perhaps was the movement’s very soul in the same way Zavattini was to neo-realism, writer Carl Mayer.

The one missing from this illustrious roll call is Henrik Galeen. Various key film reference works list him as an essential figure in German expressionism, but why do we not know him better? It can be partially explained by looking him up on the IMDb, where Galeen comes up as “writer, Nosferatu.” He did indeed write the scenario for Nosferatu. He wrote Der Golem and Waxworks, too, but who remembers that he once co-directed the 1913 version of Der Golem? Who indeed remembers him as a director at all?

He didn’t make many films as a director, and fewer still survive, but there are two that are worth tracking down. Alraune is a worthy variation on many expressionistic themes with Paul Wegener and Brigitte Helm excellent in the leads. Better is his The Student of Prague, like Der Golem a remake of a 1913 original, and while that version has its advocates, few could argue that Galeen’s is the better film.

The story is an old chestnut, essentially another Faustian reworking about a student, Balduin, who is bored with being the greatest fencer in the land and wants to turn his attention to the fairer sex, but lacks the money to do so. He thus strikes up a bargain with the mysterious Scapinelli, who promises him 600,000 ducats in exchange for just something of Scapinelli’s choice from within Balduin’s room. Balduin agrees in the belief he possesses nothing valuable, but Scapinelli claims his reflection from within the mirror. At first he doesn’t miss it, but then the reflection stars getting ideas of his own, and kills a rival in a duel which he had promised would not be fatal.

The plot being such a familiar one, and Balduin’s death foretold in the opening graveyard scene, its reputation rests on its performances and visual command. Veidt and Krauss are reunited from Caligari (they were both in Waxworks, but didn’t share a scene) and they’re both superb. Krauss’ freaky appearance, with deliberately exaggerated make-up, is quite unnerving, while Veidt is superb in one of his greatest doomed romantic roles that he often played in Germany or Britain before Hollywood typecast him as a villain. That it’s stunningly photographed in chiaroscuro worthy of the old masters and superbly designed goes without saying, as does the fact that the scene where Krauss summons Veidt’s reflection through the mirror should be as celebrated as Max Schreck on the deck of the Demeter or Rotwang’s creation of the Maria robot. Sadly all prints currently in circulation are not in the best condition – those German classics not made under the UFA banner just weren’t preserved as well – and with the original negative lost a restoration seems unlikely. Yet still its influence can be seen down the years. Take the final scene where Balduin confronts his errant reflection in his room and shoots it. The mirror shatters and he sees his reflection back on the other side through the remaining shards, only for him to then realise he’s actually shot himself. If it sounds familiar, replace the mirror with a painting, locked away in an attic, a knife through the heart.

Peter Danish’s novel ‘The Tenor’ coming from Pegasus Books

One of the greatest honors ever for Wonders in the Dark was bestowed upon the site and Yours Truly this past week, when author Peter Danish used a quote praising his book from me that is included with five others from some of the biggest names in opera. The quote will also appear on the book’s back cover. The novel, which I read months ago is stupendous, and a full review will be posted sometime after it is officially released in ten days.

The book’s trailer is offered here with the incredible inclusion of Wonders in the Dark. When trailer appears, simply click on play and wait for the five quotes, including the one for WitD, which appears at the 2:02 mark.

-S. J.

Cliff Bernunzio and his classic rock band the Nemesys at the Recovery Room; The Lego Movie; 7 Boxes and A Field in England on Monday Morning Diary (February 10)

Cliff Bernunzio and Nemesys rock the Recovery Room in Westwood

The Lego Movie figures

by Sam Juliano

As I pen this week’s lead in snow is again falling on the Metropolitan area, though expectations are that it will conclude around midnight, leaving in its wake two inches.

What can beat a glorious marathon session of classic rock from a talented veteran trio who grew up in your own back yard? The Nemesys and their erstwhile leader, bass guitarist Cliff Bernunzio rocked the rustic night club-restaurant The Recovery Room for over three hours on a frigid Saturday night in the quaint town of Westwood, New Jersey. Bernunzio, 63, and his his esteemed colleagues, Tony Cavallo on lead guitar and Chris Carnavale on drums gave the classic catalog quite the work out with three sets, that totaled 36 songs by the greatest bands in rock history: The Beatles, The Stones, The Doors, Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Tom Petty, The Yardbirds, Black Sabbath, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Queen, Steppenwolf, The Ramones, The Kinks, Simon & Garfunkle, The Zombies, John Lennon and the Steve Miller Band. As performed by the Nemesys, several of the covers were electrifying – “Magic Carpet Ride,” “I Want You,” “Brown Sugar” and “Green River” among others. All three band members alternated and/or converged on the vocals, with Carnavale assuming much of the duty in dynamic form. Bernunzio, of Little Ferry, has upcoming venues in Bayonne, in Maywood and back in Westwood in the coming months, with one devoted exclusively to Doo Wop, that will focus on Classic 45s.

The Romantic Film countdown will be pushed back one month because of the Tribeca Film Festival scheduled for mid April. Still, everyone’s Top 50 ballots will be due on April 1st. The group e mail announcement is nearing.

Lucille and I saw the following films in theaters this past week:

7 Boxes **** (Friday night) Cinema Village

A Field in England *** 1/2 (Sunday afternoon) Cinema Village

The Lego Movie **** 1/2 (Saturday afternoon) Starplex

The Paraguayan thriller 7 BOXES makes impressive use of setting to showcase an original chase tale, where the characters know little about what awaits them. For the most part this is an original and tautly constructed tale by a South American director - Juanca Maneglia - with considerable talent. He appeared at the theater from a most engaging Q and A. THE LEGO MOVIE takes its inspiration from TOY STORY, but there’s quite a bit of originality on display as well. This animated treasure is irreverent, satiric and brimming with ideas and a resounding emotional undercurrent that make this an entertainment with resonance. Directed by Phil Lord and Christopher Miller, this all seems headed to another blockbusting money franchise, which could be good or very bad. Ha! I think Jaimie Grijalba said it best when he called Ben Wheatley’s A FIELD IN ENGLAND a “head f**k” yet like Jaimie I found there was a certain degree of brilliance in this bizarre yet cinematically dazzling film by a master of this form. At some point I’d like to take in another viewing.

Caroline Kennedy’s ‘Poems to Learn by Heart,’ illustrated by Jon J. Muth

by Sam Juliano

There’s no getting around it. Caroline Kennedy’s recently-released collection Poems to Learn by Heart breathes life into a literary genre has has lost some relevance in an age of i-phones and college curriculums that have cut back on classes examining poetry. Caroline Kennedy traces her own affection for poetry back to her own reading sessions with her grandmother Rose Kennedy, who purportedly quizzed them on American history and some of the story poems that captures specific events. One, Longfellow’s beloved “Paul Revere’s Ride” was a favorite of the late Senator Edward Kennedy, who recited the marathon poem at public events. The tradition of reading poems as a family though, goes back to Jacqueline Bouvier, who met with her grandfather at least once a week to examine and recite the classics. The love for poetry was also evident at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration when he looked to Robert Frost for inspiration. Caroline herself of course published the volume A Family of Poems, a 2005 best-seller, one in which she collaborated with ace illustrator Jon J. Muth.

She and Muth again teamed up for this new volume of poetry, and the work represents some of the finest work the illustrator has ever done in a career that already has amassed some picture book classics. Muth’s magnificent Zen Shorts won a Caldecott Honor in 2006, and the talented illustrator moved on to some other distinguished picture books such Blowin’ in the Wind, a pictorial rendition of the Bob Dylan treasure, and the moving City Dog Country Frog, a collaboration with Mo Willems. Muth’s work brings fresh new visualizations to some venerated poems that date back hundreds of years. Poems by Tennyson, Shakespeare, Beckett, Chaucer, Shelley, Melville, Lincoln, Browning, Crane, Dickinson, Melville and many others are given some lovely new clothes that vividly broaden and accentuate the various interpretations, and offer the art lover some glorious watercolor paintings in this vast 200 page book that is aimed more for the higher middle school and Jr. High School students. Indeed, this collection could not be appreciated by the youngest, even if the illustrations would still captivate the gifted students in the lower age group.

The volume’s magical cover is taken from page 74, where Robert Graves’ “Id Love to Be a Fairy’s Child” is printed. Some of the most famous writings ever created are also on these pages: The famed Crispin’s Day speech from the Bard’s Henry V, Lincoln’s “Gettsyburg Address,” a passage from Ovid’s The Metamorphosis, and the General Prologue from Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. An obvious favorite of Kennedy’s is Robert Louis Stevenson, who is represented in this collection repeatedly. The poems are arranged by themes, and total an even 100. There are rhymed poems and free-verse poems, “girl” poems and “boy” poems, the latter including Yusef Komunyakaa’s “Slam, Dunk, & Hook,” Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat” and the former by Caroll’s Through a Looking Glass. Some of the poems are light and carefree, while others explore some of the darkest themes, including wars and the Holocaust. The use of the excerpts from some of literature’s most celebrated works gives the collection some philosophical heft, even if such a decision was sure to keep this volume with the older kids.

Some of own favorite marriages of words to illustration include a double page spread on Jonson’s The Masque of Queens, Ogden Nash’s “The Tale of Custard the Dragon,” and “The Lesson” by Billy Collins. But there is a unity here that makes it difficult to choose the spreads that stand out most. This is a diverse tapestry that brings into disparate seasons, terrains, countries, time periods and settings and it both engages the mind while peppering one’s sense of art appreciation with some extraordinary and expressionistic art. It’s so good in fact that it will enhance the poetry experience for most. There is a bleak undercurrent in the meditative “The Snow Man” by Wallace Stevens, a grotesque specter hanging over Prelutsky’s “Herbert Glerbert” and some irresistible humor in Neal Levin’s “Baby Ate a Microchip.” Caroline Kennedy has some great taste in poetry and poets, and though I might quibble the absence of favorites like “The Highwayman” and “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” who could argue with this collection. Simply put, it’s a treasure.

Note: This is the first in a series that will examine (mostly) exceptional non-American picture books released over the past year, and some others like today’s posting- that well warrant inclusion in the series. Though a good number of the reviews will appear on Saturdays, this won’t be exclusive.

Wonders in the Dark reaches 3 Million page views

by Sam Juliano

Wonders in the Dark crossed the finish line for 3,000,000 page views earlier today. This feat is a testament to the site’s sustained popularity as a meeting place for movie loving bloggers and many others who have come to expect the current diverse attention paid to all the arts including live theater, literature, television and music and opera.

The two most traveled threads -and both continue to get hefty hits each day- are The 50 Best Movies of the 2000′s and The 25 Greatest Opera Films with 161.000 and 26,000 hits respectively. I am proud of both those posts, especially the one on opera which continues to amaze me with its resiliency. Both the recent Best Westerns countdown and the extended series on the Caldecott Medal contenders attracted remarkable numbers as well. The most page views ever for any countdown was the one for The 70 Greatest Musicals, while the weekly voting thread that ran for almost two years achieved solid numbers as well.

I would like to thank my very dear friend Dee Dee for the miracles she has performed for this site since its inception all the way back in September of 2008. I would also like to thank dear friends like Pierre de Plume, Laurie Buchanan, Frank Gallo, Maurizio Roca, Jon Warner, Sachin Gandhi, Jim Clark, Peter M., John Greco, Pat Perry, Samuel Wilson, Jeffrey Goodman, Jaimie Grijalba, Stephen Mullen, John Grant, Jaimie Grijalba, Mark Smith, Dean Treadway, Judy Geater, Patricia Hamilton, Terrill Welch, Murderous Ink,Tim McCoy, David Noack, Ed Howard, Bob Clark, Brandie Ashe, Duane Porter, Shubhajit Lahiri, David Schleicher, Jason Marshall, Mike Norton, Celeste Fenster, Joel Bocko, Dennis Polifroni, Marilyn Ferdinand, Roderick Heath, Peter Lenihan, Stephen Morton, Just Another Film Buff, Jason Giampietro, Drew McIntosh, Michael Harford, R.D. Finch, Adam Zanzie, Hokahey, J.D. La France, Dave Hicks, Stephen Russell-Gebbett, Kaleem Hasan, Pedro Silva, Anukbav, Movie Fan, Kevin Deaney, Longman Oz, Troy and Kevin Olson, Rick Olson, Jason Bellamy, Joe, John R., Karen, Broadway Bob, sirrefevas, and of course to Allan Fish for collectively bringing this place sustained activity and prominence. My longtime friend from Down Under, Tony d’Ambra has helped this site above and beyond and has remained an unwavering and dependable friend all the way to the time we first unveiled this place to the public eye.

It’s been an amazing ride, and I dare say it’s far from over. Thanks my friends!

Below are the top posts as copied from word press:

Gloria, Young Mr. Lincoln, Oscar Nominated Animated Shorts and upcoming ‘The Complete Hitchcock’ on Monday Morning Diary (February 17)

One of the most extraordinary animated short film line-ups ever to compete for the Oscar

Henry Fonda as ‘Young Mr. Lincoln’ screened at Film Forum on Sunday

by Sam Juliano

How like a winter hath my absence been

From thee, the pleasure of the fleeting year!

What freezings have I felt, what dark days seen!

What old December’s bareness every where!

-William Shakespeare, “Sonnet 97″

Every state in the nation has been visited by the ultimate barometer of winter -that once welcome, but now tiring and meddlesome white marauder- over the past week, except for Florida. In the now beleaguered northeast it has been a conveyor belt of storms and frigid temperatures, and the latest word is that we may not yet be done. Certainly our dear Midwestern brethren have suffered through the darkest season in many a year, and there has been some catastrophic weather in parts of the United Kingdom. March inches closer, but can anyone feel safe until April Fool’s Day or even then in this season of uncertainty and vulnerability. Amidst all the mayhem, some school districts -including our own in Fairview- are closed for President’s Week, allowing for some recovery and/or meditative time.

The e mail chain for the Romantic Film Countdown polling will be sent out to all e mail members this coming Wednesday, February 19. Those casting ballots will have until April 1st to vote and send on to the network. While it has admittedly taken quite a bit of time to get this project off the ground for various diversions and considerations, I am (personally) ready to move forward and am very excited. Hopefully a good number of friends and readers are of the same mind-set.

One of the most incredible and most comprehensive Film Festivals ever staged anywhere or anytime will be commencing at the Film Forum on Friday, February 21st, and will continue for five full weeks. The Festival has been titled The Complete Hitchcock and the schedule will include every feature length film the prolific Hitch ever made, including the ultra-rare German-language MARY (1930) and his nine surviving silents, all restored by the BFI. Lucille, young Sammy and Danny and I will be on hand for a fair number of these screenings, including a few attractively-paired double features for the price of one. A more glorious tribute to Hitch than this one? I doubt it. Here is the link to the full Film Forum schedule:

http://www.filmforum.org/movies/more/the_complete_hitchcock#nowplaying

In any case, after the Complete Hitchcock concludes on March 27, the Film Forum will then stage a complete festival on Francois Truffaut and a 60th Anniversary restoration of Godzilla. Happy times for movie lovers in New York City for the upcoming months. Presently, Godard’s Alphaville and Resnais’s Je T’Aime Je T’Aime are playing on separate screens until Thursday.

Dennis Polifroni, young Sammy and Yours Truly will be recording our annual Oscar Predictions video at the local Boulevard Diner on Monday evening, February 24th. The you tube video will be the first time be filmed and edited by the talented Miss Melanie Juliano, though the wily Oscar veteran Jason Giampietro may be on hand with a second camera. The finished product will be posted at the site on either Wednesday or Thursday of that pre-Oscar week.

While the beginning and middle of this past week was spent watching the multiple storms unfold from home and shoveling out from the aftermath, Lucille and I (and young Sammy as well) still manged to take in three movie presentations in theaters over the weekend, somehow negotiating the challenging road conditions. We took in:

Gloria **** (Friday night) Montclair Bow-Tie Cinemas

Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) ***** (Sunday) Film Forum

Oscar Nominated Animated Shorts ***** (Saturday) Bow-Tie

Sebastian Lelio’s focused Chilean drama GLORIA about mid-life crisis and eventual rejuvenation owes some thematic debt to the character Gena Rowlands played for Cassevettes, but the film has a naturalist spontaneity and honesty that forges its own path, bolstered by an absolutely extraordinary performance by Paulina Garcia, who pulls away from mid-life crisis doldrums to finally celebrate life for a new found vitality. Jaimie Grijalba wrote a fantastic review of it at Overlook’s Corridor, which I have linked here:

http://overlookhotelfilm.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/chilean-cinema-2013-12-gloria-2013/

This year’s crop of Oscar-nominated Animated shorts is the strongest for any year I can remember, and I am presently unable to select a favorite – all are excellent, and the three others that were shown that apparently “just missed” have complicated the issue further as all of those are terrific as well. One of those three that missed the cut – the often hysterical French A La Francaise about a gaggle of chickens running King Louie’s court matches the best of the best here. The American Feral, a lush and entrancing tale about a child raised by wolves and later found in the wilderness to be domesticated, has the look of a moving oil painting, and the color is both stark and vibrant. Emotionally it is unquestionably the most resonant of the lot. Simon Pegg’s utterly winning narration for the British Room on the Broom, based on the children’s book of the same name establishes added heft to this oddly engaging story of a witch who assembles a group of animals to fly the skies with her. At about 30 minutes this is the longest short, and the one that may snare the Oscar in the end. The way I am seeing it now the race is neck and neck between Room and the Pixaresque story Mr. Hublot, about a robot and a dog in a machine city. As to the other two nominees, Get A Horse is a Disney homage to the classic “Mickey saves Minnie” and the Japanese Possessions, (the favorite of my son Sammy) tells a story of a fix-it man who chances upon a temple during a storm. The amime style here is the real allure.

John Ford’s masterful 1939 classic Young Mr. Lincoln was screened on Sunday morning at 11:00 as part of it’s popular “Film Forum Jr.” series, and a very special treat awaited those who attended. The esteemed screenwriter and playwright Tony Kushner (who penned the screenplay to last year’s Lincoln) was on hand to introduce the film, which he identified as one of his favorite by the director he referred to as “America’s all-time greatest.” One can never tire of Young Mr. Lincoln, and every new viewing will invariably set one off on yet another study of the most studied of all historical figures. It was great introducing Sammy to the film -he loved it as expected- and to again revel in the superlative craftsmanship and rhythm and in one of the greatest of performances by Henry Fonda as a youthful Abe. The best reference point ever on this great film is the now-famous and incomparably passionate statement from Sergei Eisenstein:

Suppose some truant good fairy were to ask me, “As I’m not employed just now, perhaps there’s some small magic job I could do for you, Sergei Mikhailovich? Is there some American film that you’d like me to make you the author of – with a wave of my wand?”

I would not hesitate to accept the offer, and I would at once name the film that I wish I had made. It would be ‘Young Mr. Lincoln’ directed by John Ford. There are films that are richer and more effective. There are films that are presented with more entertainment and charm. Ford himself has made more extraordinary films than this one. Connoisseurs might well prefer ‘The Informer’ (1935). Audiences would probably vote for ‘Stagecoach’ (1939) and sociologists for ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ (1940). ’Young Mr. Lincoln’ didn’t even get one of those bronze Oscars. Nevertheless, of all American films made up to now, this is the film that I would wish, most of all, to have made. What is there in it that makes me love it so? It has a quality, a quality that every work of art must have – an astonishing harmony of all its component parts, a really amazing harmony as a whole………..I saw this film on the eve of the world war. It immediately enthralled me with the perfection of its harmony and the rare skill with which it employed all the expressive means at its disposal. And most of all for the solution of Lincoln’s image. My love for this film has neither cooled nor been forgotten. It grows stronger and the film itself grows more and more dear to me.

I am happy to have links up for this week:

At Tuesdays with Laurie, the indomitable Ms. Buchanan is the subject of another great and deserving honor: http://tuesdayswithlaurie.com/2014/02/12/words-of-wisdom-from-laurie-buchanan/

At Noirish the exceedingly gifted and prolific author John Grant has penned an especially excellent review of the little seen Stanley Kramer debut film “Not as a Stranger”: http://noirencyclopedia.wordpress.com/2014/02/15/morton-thompsons-not-as-a-stranger-1955/

Stephen Mullen (Weeping Sam) has declared “Inside Llewyn Davis” as the best film of 2013 and one of the Coens’ most formidable works at The Listening Ear: http://listeningear.blogspot.com/2014/02/inside-llewyn-davis.html

Dean Treadway continues his fabulous annual cinematic coverage with an in-depth look at 1927 at Filmacability: http://filmicability.blogspot.com/2014/02/1927-year-in-review.html

Judy Geater has launched her new series on Douglas Sirk at Movie Classics with a terrific essays on “Has Anybody Seen My Gal?”: http://movieclassics.wordpress.com/2014/02/16/has-anybody-seen-my-gal-douglas-sirk-1952/

John Greco has written a superb review of Luchino Visconti’s extraordinary “Bellissima” at Twenty Four Frames: http://twentyfourframes.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/belissima-1952-visconti-luchino/

At Scribbles and Ramblings Sachin Gandhi has the South American Movie World Cup pairings up for your perusal: http://likhna.blogspot.com/2014/01/south-american-films.html

At Overlook’s Corridor Jaimie Grijalba is up to “screenplays” in the continuing examination of his annual ‘Frank Awards’ given to the best films and components: http://overlookhotelfilm.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/frank-awards-2013-screenplays/

Pat Perry’s latest post at Doodad Kind of Town superbly addresses “Philomena” and “Inside Llewyn Davis”: http://doodadkindoftown.blogspot.com/2014/01/surprise-surprise.html

At Dee Dee’s ‘Ning’ network site she has posted some spectacular and rare Hitchcock posters in honor of the Film Forum’s great Festival on the prolific icon: http://filmnoire.ning.com/forum/topics/darkness-before-dawn-takes-a-peek-at-foreign-posters-and

Jon Warner has posted a fantastic essay on the documentary masterwork “The Act of Killing” at Films Worth Watching: http://filmsworthwatching.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-act-of-killing-2012-directed-by.html

At FilmsNoir.net Allan Fassions has written a superb essay on 1955′s “Dementia” for the site’s erstwhile proprietor Tony d’Ambra: http://filmsnoir.net/film_noir/alan-fassioms-on-dementia-1955-beatnik-noir.html

And speaking of Fassions, his site is now the latest inclusion on the WitD sidebar. It is called “Stranger on the 3rd Floor” and it looks like a fabulous place to visit: http://strangeronthe3rdfloor.wordpress.com/

At The Last Lullaby filmmaker Jeffrey Goodman is leading up with his 12 Best Films of 2013: http://cahierspositif.blogspot.com/2014/01/my-top-twelve-films-of-2013.html

The great Canadian artist Terrill Welch is leading up at her sublime Creativepotager’s blog with a post titled “One Brush Stroke After Another”: http://creativepotager.wordpress.com/2014/02/10/one-brushstroke-after-another/

As ever, Samuel Wilson is posting superb reviews that may have esaped the radar. His latest great piece to that end at Mondo 70 is an essay on “Greed in the Sun”: http://mondo70.blogspot.com/2014/02/greed-inthe-sun-cent-mille-dollars-au.html

Patricia Hamilton has written a tremendous book review on Anish Majumdar’s “The Isolation Door” at Patricia’s Wisdom, and the author chimed in: http://patriciaswisdom.com/2014/02/the-isolation-door-a-novel-anish-majumdar/

Shubhajit Lahiri has penned a provocative capsule on the Argentinian film “Wake Up Love” at Cinemascope: http://cliched-monologues.blogspot.com/2014/02/wake-up-love-despabilate-amor-1996.html

David Schleicher has penned a fabulous review of the Iranian “The Past” at The Schleicher Spin: http://theschleicherspin.com/2014/02/09/secrets-and-lies-in-the-past/

Brandie Ashe has posted a wonderful post on Shirley Temple at True Classics: http://trueclassics.net/2014/02/11/remembering-shirley-temple/

Mike Norton has penned some superlative pieces on Hip Hop at Enter the Screen: http://enterthescreen.wordpress.com/

Joel Bocko posts about the screen-capping he’s managed over the past year at The Dancing Image: http://thedancingimage.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-final-watchlistscreencap-some-notes.html

Roderick Heath brings unprecedented scholarship to Ivan Reitman’s “Ghostbusters” at Ferdy-on-Films: http://www.ferdyonfilms.com/2014/ghostbusters-1984/21071/

J.D. LaFrance leads up with a terrific review on “Neuromancer” at Radiator Heaven: http://rheaven.blogspot.com/2014/02/neuromancer.html

Drew McIntosh has again offered up a fascinating post at The Blue Vial, showcasing works by Walerian Borowczyk and David Lynch: http://thebluevial.blogspot.com/2014/01/end-of-road.html

Marvelous and wistful picture book ‘Hello Mr. Hulot’ suffused with cinematic energy

by Sam Juliano

The indefatigable “Mr. Hulot”, who appeared in four of Jacques Tati’s films is one of the cinema’s most venerable creations. First published in France under the title Hello Monsieur Hulot David Merveile’s sublime and utterly delightful picture book Hello Mr. Hulot is a labor of love by a lifelong fan of the iconic character, Jacques Tati’s tragic-comic alter ego. A pace gone awry, technological advancements and the inevitably complex transportation system make life difficult for the gauche and blundering Hulot, whose most distinctive attributes center around his dress. His short trousers and wrinkled coat, striped socks and trademark pipe, hat and umbrella have established a singular identification. While never matching the universal love and recognition afforded Chaplin’s tramp or Keaton’s stone face, he has persevered in the shadow of the cold and inhuman modern society he mocked with a unrepentant quixotic glee, as one of the greatest comic creations in the history of the cinema.

Hulot was featured successively in Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1959), Play Time (1967) and Traffic (1971). Author Melville claims he caught Hulot fever in 2004 after hiding a drawing of the iconic character in one of his illustrations, and then getting many responses from fans. Merville adds: “Translating Tati’s films into the genre of the picture book seemed very logical to me: I could actually silhouette the behavior and gestures of Monsieur Hulot. It’s ideal for a paper copy. The great film posters from Pierre Etaix demonstrated this. Also, Tati’s access to film, his love for details, his keen powers of observation, his interest in things, his feelings about architecture, his economical use of dialogue, and his visual jokes have all encouraged me to develop Monsieur Hulot on paper.”

The book features delightfully colorful and witty comic strip-style illustrations depicting twenty-two alluring scenes with a page turn that showcases a surprise ending the narrative panels that precede it. In one gem titled “Pipes Allowed” Hulot’s incessant pipe smoking in an increasingly hostile environment plays out on a bus where a woman angrily points to a no-smoking sign while surrenders as bubbles flow from his pipe, amusing the woman’s young child. In the full page denouement bubbles seem to emanate from all sources in front of a French cafe – they rise from the popsicles being enjoyed from a young couple, one fills in for a balloon being held on a string carried by a child and they form speech bubbles for conversing patrons.

One of my own personal favorites, “Hulot the Plumber” is one that vigorously recalls the 1940 Del-Lord directed Three Stooges classic “A Plumbing We Will Go” which chronicles the bumbling antics of a clueless Curly, whose idea of fixing a leak is to complicate the situation with far more damaging consequences. Hulot the Plumber comes upon the scene after drips are heard in the kitchen of an apartment building. By utilyzing a mis-directed red hose the bumbling Hulot even manages to intermingle the water and electricity (as the boys in “A Plumbing We Will Go” did with anarchic hilarity) before a temporary reprieve leaves his smugly reading a book while disaster looms by way in the matter of a building completely flooded, with a geyser rising from a chimney, and others trying to save themselves in various manners from the flooding.

Chaos of a different flavor plays out in two other clever vignettes. ”The Snowball Effect” first spies our hero innocently walking on a snow covered sidewalk, where he is subsequently pelted by a snowball thrown by a quickly enough revealed mischief hunter. Always the obliging one, Hulot retaliates in kind, but accidentally hits another, while crossfire develops, culminating in the final spread of a street gone haywire with many game to engage in the mayhem. In “Urban Symphony” Hulot is regaled in succession by a boom boxer, a car wildly honking, the grating rat-a-tat of a jackhammer, the sloshing of a street cleaner, the clanging of a man hole cover and the roar of a truck, before noises of every kind converge in a scene that exasperates and even deafens the perpetrators. Hulot’s inherent kindness and solitude surface in “The Umbrella Corner” and “Valentine’s Day.” In the former he shelters a group of birds under his umbrella as rains begins to fall. After the bus pulls up he decides to leave behind the umbrella, which becomes wedged between branches in a tree to serve as a cover for the flock. In the latter series, our everyman ventures upon couples celebrating and toasting their romances, and finally leaves in the rain, with his shadow offering flowers to a woman on a building poster. Merveille’s use of muted colors and lighting is very effective in this melancholic tapestry.

Other memorable vignettes include “The Heart of Paris,” “French Riviera”, “Hulot the Hero”, “Don Quixote” and especially “Chameleon” when Hulot finds physical and ornamental kinship with a penguin, an iguana, a butterfly display, bats hanging in a cave and a raccoon before unconsciously aping the physical positions of a group of flamingos. Much like his cinematic incarnation the Hulot who is at the center of this book’s adventure is a sad figure, and there is a wistfulness that suffuses the vignettes. There is droll humor, more than a dash of irony and the underlining heroic stature that defined this iconic figure. The book proceeds with the kind of cinematic energy and engagement that would make Tati proud.

NorthSouth books 56 pp. $17.95

Note: This is the second entry in a continuing series that will examine non-American picture books of a high level of artistry and creativity that were released during 2013. The series will also include a few special items and recent releases.

NICOLAS REFN’S VALHALLA RISING “What do you see?”

© 2014 by James Clark

When we come to a film as bizarre as Nicolas Refn’s Valhalla Rising (2009), we are, perhaps unbeknown, placed within large demands to get to the bottom of its expressive design. The work appears at first glance to be a study of sorts concerning the ways of Nordic tribes in the late medieval period (say, 1000 AD) where a pagan (Viking?) ethos finds itself troublesomely confronted by the clerkish circumspection of bands galvanized by Christianity. At the outset, we are put on notice, along such lines, by this signage: “In the beginning there was only man and nature. Men came bearing crosses and drove the heathen to the fringes of the earth.” Judging from the Scottish dialect of the non-heathens here, we would seem to be dipping into the ethnology of early Britain. (Valhalla Rising was in fact filmed in Scotland, spilling our way as concentrated a swatch of disturbing atmosphere as you’re ever apt to see—unremittingly dark and damp and stark, with winds close to blowing the cast off of the planet, reminding us of the inclement features of Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, filmed in another weather hell, Canada.)

But if the concern of Valhalla Rising were at all driven by the romance of history, we would not, surely, see so much Gothically chic wardrobe—not unlike the garb on display in expensive, media-zone restaurants. Nor would we have a camera-angle, during a tense confrontation, where the protagonist’s battle axe is poised like a big pistol in a holster. Nor would we have a Man with no Voice, unmistakably giving off a (highly inflected, of course) version of the Man with No Name. (Actor, Mads Mikkelsen, provides a similarly handsome tautness of skin and expressivity of eye.) The protagonist’s loyal companion, a young boy with Scandinavian hair, tells him, during one of the myriad tight spots they occupy, “You need a name. You’ve only got one eye…” This near-banter within a narrative plunge so heavily steeped in violent death, while seeming to fit nicely within the glory days of Clint Eastwood, does, in fact, bring us to the point of realization that Valhalla Rising no more closely stalks early film than it stalks early history. (For good measure, Refn has apparently done his bit to muddy the waters by referring to this movie as “science fiction,” especially thrilled by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

The quip about needing a name sends us to the business of a figure, mute, but on close inspection fully aware of the conversation coming his way, and having devised a strategy to disarm it. His silence, as I think we’ll come to recognize, is as formidable a weapon as his bare hands and his axe—and, in that, it comprises a double edged sword, a trusty stabilization in a context of deadly derangement; and an atrophied medium of interpersonal discovery. His having only one eye (presumably gouged out at an earlier stage of his enforced practise of the craft of kill-or-be-killed-exhibitions for a market in need of couth) silently speaks to that far less evident and far less readily comprehended deficit.

Let’s, then, begin by way of that scene where the boy points out to him that minimalism can be carried too far. They’ve escaped, in a shower of enemy blood, from the porn circuit and have come upon an encampment of pious Celts, where in fact their leader is on his knees in prayer before a cross. (Also catching our eye is a group of women huddled together under an armed guard—disconcertingly naked [McCabe’s dismal early brothel pops up] in that frigid air, and somehow missing out on the demonstrative delicacy as advertised.) The chubby attendant to that early YWCA blurts out that, “He’s one of the biggest savages in Sutherland… He killed our chieftain’s son… most of his men as well…” That displaced swordsman lets us in on details of the film’s outset, showing how the professional blood sport has become a staple in that territory. But even more to the point, he takes his place as one of a panoply of straight men in this settlement, to the minimal black comedy our protagonist displays a powerful flair with. From the moment that quasi-ventriloquist-team comes into view, its singular micro-climate induces the anal rustics to exorcize them along lines of reciting their ownership of a multifaceted bulwark against every dangerous feature intrinsic to existence. The chieftain leads off with, “Are you from the clans, Warrior?” It is the boy who hesitatingly says, “No,” an interactive peculiarity that especially prompts the edgy leader to demand, “Why does the boy speak for ya?” One Eye fixes him with a suspenseful glare, establishing the ground rules as he understands them to involve deadly (if necessary) resoluteness always having the advantage. His frustration and anxiety mounting, the local alpha barks out, “You Christians?” And after a pause, uncomfortable to the little blonde, his androgynous demeanor being a special irritant in a patriarchal orbit, he replies quietly, “Yes.” Pulling his sword out of the mud where he’d parked it during prayers, the commander snarls, “Yer lyin’,” calls to his son, who approaches, locks eyes with One Eye and his gunslinger axe-angle, takes out his sword, notes with shock that his adversary pictures him as already a corpse—and, with a funereal-apt raw glint hanging over the moors, his father steps up and the boy withdraws. Now exposed as not competent for conflict, the leader retreats with a touch of patently empty bravado—“Does the mute have a name?”—to which the young boy (now more than ever a page) replies, “His name is One Eye.” (Seeing his unofficial master less than pleased with that invention, he reasons, “You only have one eye;” but with the harder truth, “You need a name,” he proves he belongs, rendering in fact a fundamental reminder about the gallantry, the creative recognition of others, implicit in the discharge of his fighting efficiencies.) “One Eye, ye can eat with us,” is where things go next, and during the meal, while the Man with a New Name silently disses these self-assertive nuisances, both poles of this confrontation are looking for what they can exploit from the other.

The setting of this dinner is arresting: almost complete darkness with not so much as an ember to evoke the merest spark of interaction, and everyone seated on the absolutely unattractive moor. The convenor asks, “So, how did you get your freedom? What do you plan to do with it?” One Eye imperiously looks toward the topography, pointedly stressing his seeing that the fretful hosts know nothing about freedom and are whistling Dixie if they think he owes them any accounts of his priorities. The flaccidity of these correspondents confirms him in a sufficiency of communing with his own carnal composure. The Sutherland body-counter suggests, “Maybe he could bring us luck;” and the commander follows with, “I could use a good fighter like you… We’re God’s own soldiers, Warrior. Heading to Jerusalem to reconquer the Holy Land…” The look on One Eye’s face at this moment can only be well comprehended with regard to the time of his captivity, when—confined to a wooden cage and with shackles trailing from an iron collar, and then taken out to fight for his life while being chained to a pole like a bear in a bear pit—attending to that indispensable composure and efficacy afforded by silence was all that could make sense to him. Now prodded by garrulous cowards, he would assimilate the desperation and volume of the rhetoric as both contemptible and ludicrous; but there would be something more than a sterile standoff. “There’s great honor in it [the reconquest]… riches, land” [and here the boy looks over at One Eye, and the look on his face is to communicate his strong desire for avoiding violent rupture. He told the leader, “I wanna go home.../ “Where is that?”/ “Dunno...”]. Another greybeard, but with a more agile fluency, regarding the warrior’s being underwhelmed by the chief’s pitch (we see One Eye in close-up and in profile, and the speaker is some distance removed, leaning on a boulder), declares, “Endless warfare [capturing a bit of interest]… But it makes more tramps than heroes…But you should come with us to Jerusalem. Yer sins will be absolved, whether you live or die. Ye will see yer loved ones again.”

Though most viewers come away from Valhalla Rising with the priority of having seen “senseless violence” (perhaps even more viewers come away from it with that idea in having avoided seeing it at all), I maintain that it is a compelling reflective drama, written and produced with rewarding verve. As we complete our survey of a passage valuable in navigating exactly where this far from straightforward or simplistic movie is going, we should notice that the boy with scraggly blonde locks often covering his face progresses, in light of the sustained poise of his companion being at perfect pitch for the occasion, to a bit of playful intimidation of his own. Someone from out of that celebratory gloom asks, “Boy! Where does he come from?” After thinking a moment, he declares, “He was brought up from hell…” We see the supposed hellion in profile, and off a ways someone asks, “So where is this hell?” And the boy pipes up, “On the other side of the ocean…” Perhaps twigging to the fact that they are being ridiculed by the kid, the locals, led by the theologically erudite second-in-command, return to the unearthly prize which One Eye represents to them. “It’s more than revenge… all these things go… You should consider your soul… That’s where the real pain lies…” With this, One Eye turns and looks hard into the speaker’s face. Then we are face on and up close to the stranger. Something more than contempt informs his stance.

That his pensive profile as becoming a pensive face-on amidst the darkest of clouds, the most shattered of moors and the shrieking gales transposes to the rippling waves in a Scottish bay at the beginning of a huge gamble that represents his only move, has to be bolstered here by introductory action we’ve left until now. One Eye and the boy, the most unlikely of crusaders, have to be introduced as the most desperately isolated and besieged of voyagers. Far from a government-endorsed space odyssey affording adventuring in the grand style, theirs is practically the quintessence of that “tight spot” the Coens’ Ulysses makes a mockery of. As we proceed with details of their truly epic and thereby truly revealing distress, we are, when looked at trenchantly enough, truly engaged by Refn’s wildly inflected researches in “science fiction.”

So now is the time to pull away from the badinage which defines our protagonists as earthy outsiders, to savor for a moment the quite unique intensity of a state of “home” requiring improvement. The first shot—showing a figure (the boy) at long distance trudging along a hillside with a pail of water, almost completely lost in thick fog and almost swallowed up by the impenetrable darkness of the moors—keys the narrative setting in such a way as to emphasize that we have entered a protagonistic field where the human and the non-human meet in an uncanny, dangerous interplay. Even before we clearly focus on our main figures, then, we are aware that names are startlingly irrelevant. The insistent ringing motif complements that fusion, with the added factors of mortal danger and stunning hostility. The recipient of the water is not only locked into a timber-sided cage; his hands are bound, and as we regard that condition we can see that animal-like tattoo images invade his arms and back. This situation unfolds to an action of the boy’s tending to open wounds on his charge’s back. His being restrained, during these attentions, by chains trailing from his neck further installs into the viewer’s startlement, at such a state of distemper, that this figure has more in common with wild beasts than with the human community and its discharge of security measures as crude as they are mawkish. The lumpen guards are insinuated, by these means, into a base facsimile of the prisoner, in his carnal integrity, and the boy, raptly applying a black poultice to the sores. Therefore, as the next scene explodes in our face, showing the leashed warrior smashing an overturned opponent repeatedly, to the sounds of broken bones, there is a panning shot displaying the promoters of this mayhem, crumpled like anxious fungi as seated around the battlefield. A monkey-like local with a blanket over his shoulders comes up to an authority-type, receives some coins and wobbles through the assembly, stopping to give some of the handicapped money to a bettor. There is more such testing of One Eye’s physical powers, his being a creature conversant with a battle terrain of wet muck and with deploying his body to destroy an alien body. But the point to especially concentrate upon is the aftermath of two more (Sutherlanders’?) crushed skulls, when the one-eyed survivor, being tethered to return to his outer-limits home, holds out his hands, fists clenched. With that gesture, he traces the intensive concentration that defines his days; and, moreover, he touches upon the reversal of that tightness, a flux in proximity to the readily overlooked graces of that ominous highland. The elder who payed out the winnings comes to the cage with a sour visage. We notice with some surprise another such pen, in the distance. We also note a bit more brightness in the gloom. One Eye calmly glares back at such a cheap master. But, in fact, master no more, as the following scene has another aspirant (in fact the fungus paid off by the monkey) to stage such tempestuous theatre and wagering. The latter tells the sour one, “You’re time has passed… Mine has come…”

The transfer of One Eye develops in many fresh ways the scenario’s bringing about a strange planet with its divide between those who only grasp and those whose grasp becomes part of a startling equilibrium. The episode begins with One Eye asleep in his cage, the wind howling. He dreams of a river of blood, and then he is chest-deep in it, the river shimmering, and rocks on both shores. The dream includes his taking a big rock and bashing in the skull of an enemy with it—a brutal materiality of slaughter ensuring that his purchase upon equilibrium could not be divested of its nightmarish associations. Heavily chained and guarded, he is seen in a column lunging across difficult terrain in that terrible wind. He is intent and calm as he surveys a promising volatility. Allowed to be watered like a horse, in a pool of shimmering, clear water, he stands chest-deep in a new avenue for action. The boy watches him from the shore, his concern very distinct from that of the guards also on hand. What with the clean water trumping the bloody waves in his dream (just as the boy trumps the jailors), he occupies a zone of absolute silence and stillness. Then he looks down into the water, sees something promising for a change and submerges toward it (not unlike finding couth where hitherto it was savagery all the way). Picking up an ancient arrowhead, he studies it for a bit, underwater, savoring the beauty of its lines and texture, and its useful aspects; and then he puts it in his mouth and surfaces to face those he has to defeat. At night he studies his gift from the world-wide world, from one far-away expert to another. He tests its sharpness by cutting his hand with it, after which he clenches his fist on the wound. As he fills his heart in this way, the outmanoeuvred old pagan rails against his prevailing rival—“Bastards! Eat his flesh. Drink his blood. Abominable! We pray to the gods to protect us… We have many gods. They’ve only got the one! Won’t let him go. We need him…” And the rival rubs it in, his white-collar violence a rational component of the dead ends facing our protagonist. “You need money… like everyone else…It’s the only way to reason with the Christians… You might as well get it from me.” They shake hands, and the new force clenches his fists, looking across an infinite gulf to the fighter, who is even more proudly silent than we saw him before.

In accordance with the new ownership, One Eye travels with his head covered by a black cloth. The cloth has protuberances that resemble ears. Donkey ears! He strides across that terrain and his legs are closely filmed; they are greyish and the texture of the covering of a quadruped. He begins to free with that sharp edge his neck restraints under that convenient and thought-provoking temporary skin. Ripping off his mask, he’s on track to be much more like the tiger than the donkey. (And yet, has there ever been a more Balthazar-like beast of burden, showing seemingly endless capacity to endure hardship? Balthazar, though, you may recall, was also devoted to sharing love, the big question mark posed by this film.) Quickly acquiring an axe, he uses it very effectively and before you know it he’s not only a free agent but he has tied to a rock one of those too petrified to challenge him or run away. The captive has no eye for One Eye’s slight progress toward buoyancy. Surprisingly for so inept a warrior, this diminutive road kill has quite a mouth on him. He rudely rallies the former slave and lax communicator, with, “What do you see? When I die, you will go back to hell.” Having spent years being insultingly categorized as lacking valuable perceptive traction (while in fact not being one to miss the point that everyone around him is far from impressive), he performs an execution of that vox populi which, while clearly lacking Arthurian gallantry, constitutes a bellwether of sorts concerning a toxic irritant much more, in fact, germane to the twenty-first than to the eleventh century. As a means of measuring how confined he remains within that “endless [physical] warfare,” he comes up to the cheeky prisoner and with his bare hands rips out his guts, plopping them on the unfertile land like a load of fertilizer. We are given a close look at one of the victim’s hands, quivering and then freezing, very unlike the kinetic expertise of the outsider having come to relish savaging those precious smartasses on the other side. The kiss-off from a life having been unspeakably annoying consists of mounting the head of one of those mainstream underachievers at the top of one of those neck-bars that would always have been a presence of his routines. Their partnership now on new footing, the boy shows him a ring and asks (not so puzzlingly in view of One Eye’s appreciation of fine craft), “Do you like it? My father gave it to me…” But now the escapee has turned to the dilemma of nowhere to turn; coming to his imagination is his face smeared with blood. Also he considers the sea as a way to rejuvenate his hitherto cramped, humiliating endeavors.

Coming upon those quixotic sailors and their cut-and-dried travel objectives, One Eye bids to make the best of a long-shot. In accordance with the farcical incompetence of his new associates, the ship promptly runs across a protracted passage of doldrums (where the setting is like a liquid desert). The old theoretician, kindly enough thinking to relieve the discomfort of the only child onboard, tells the little stranger (who has, as we know, seen much worse), “Do you know what I do when I’m scared?” [for instance, now]… The boy, whose repertoire of equilibrium does not run to panaceas, shakes his head at this puzzling juncture. And that elicits the emergency supply, “I pray to Christ.” On seeing how puzzled and noncommittal the mascot is, the officer asks, “Do you know who he is?” The boy shakes his head again, no longer feeling compelled to butter up a fighting force which One Eye has effectively subdued. “He sacrificed his life so that we could be free… from pain and misery… So you have to be strong…” The boy does not need such a reminder, and it shows. Moreover, One Eye, who had been listening close by, makes a gesture (cut mid-way) of spitting on the floor in face of this presumptuous authority. Both of them, then, at this point, are impervious to the prospect of giving the time of day (mustering a loving sacrifice of their self-sufficiency) to hated enemies, as propelling life forward. This quiet display of repulsion is not lost upon the rest of the crew perched about the deck in a prostration resembling a diseased aviary. Soon the impulsive former attendant to the ladies is thinking out loud, “Perhaps it’s a curse.” During prayers for delivery away from a deadening sunlight haze, the one who floated the idea of a curse (only to be rebutted by the chief) notices how indifferent the two strangers are. So, on the heels of another bloody nightmare visiting One Eye, the obsessive tells his mates, in focusing on the far more easily managed child, “I’m gonna kill him.” Another action hero steps forward, declaring, I’ll do it,” but before he can use his dagger One Eye has chopped a hole in his torso and thrown his corpse overboard. The leader tells his noisily upset crew, “Back off!” And while the complaining from them goes nowhere, the situation of our protagonists’ alienation has been underlined once again, in order that the eventful saga of the destination not lead to blind alleys.

Before the wind does get back to business, and the little ship ends up somewhere (though not Jerusalem), the chief, true-blue dour Scot that he is, recalls, “The boy said he was from hell,” and infers, “Maybe that’s where we’re going.” And though several Canadians might concur in the epithet, “hell,” the scene does in fact shift to a Scottish facsimile of the Labrador/Newfoundland coast, in the form of a sparkling blue estuary with skies of hitherto unseen blue and pine forests and sub-Arctic meadows all round. Though miffed from many angles, the crusaders, led by the somehow charismatic chief and his theological advisor, seamlessly (Celtic whimsy in full force) shift into taking this clearly Nordic locale for the Holy Land. (For all the blood-curdling pistons of his scenarios, Refn is an impressive exponent of situational comedy.) There is, however, also, about this flood of bracing landscape, an indicator, at a subliminal pitch, that our protagonists now occupy a terrain where the constraints upon their bringing into play an opening of the clenched fist have been somewhat relaxed. After the spate of compulsive, self-justifying chatter with which the crusaders have bombarded the strangers and us, we now effectively occupy an expressive zone closely resembling dance and its special investigation of the challenges and rewards implicit in silent motion. At the early stages of the scouting mission on foot, anticipation begins to take on the property of malaise, inasmuch as they come upon wooden platforms (vaguely echoing One Eye’s cage) where corpses lie, perhaps implying famine. One Eye, now more in the capacity of Swiss Guard than a reluctant novice/companion to the elect, tensely surveys the hinterland of this oddly callous statement. The chief says, “I’m gonna show them a man of God has arrived;” but One Eye is no longer absorbed by obviating him. He interrupts a circle of silent prayer by plunging the sword of a crewman, who had ventured off alone, into the soil. “Where did you get that?” someone asks. One Eye barely notices such impertinence, his attention galvanized by his and the boy’s project now beginning to crash and burn. The fat loudmouth offers, “You killed him!” One Eye doesn’t even look his way, his attention in fact focused on the river below their vantage point. The leader commands them to row the ship further upstream, to “find out where we are…” One Eye joins in the rowing, a moment of unity at a point he knows to be a foolish venture. Soon an arrow rips into a crusader, blood gushing and much howling. The boy is horrified; One Eye impassively looks into the dimension of death; and the crew, swords drawn (clearly the wrong weapon) commences what spins from a military to a mystical exercise. Were the point to simply exterminate the invaders, more arrows would be flying. One Eye becomes dead calm (the boy still distraught) in realizing that he’s become once again part of a sadistic entertainment. (The owner of the sword One Eye put into the puzzle does show up, stripped, painted upon and quite insane.)

Now expecting death to strike them at any moment, the entire invading force silently plays out a series of bizarre personal observances. That One Eye and the boy also come within this thrust places them in a highly inflected context of kinship with vastly unforthcoming traditionalists. One Eye washes the blood from the arrow that depleted the crusade. The design beauties of the arrowhead in the pool are clearly invoked again, for their resonant powers. Though the leader can’t resist revealing a perdurant ideological insanity (“We claim this land…”), many of his followers dispense with doctrine and enact primal, almost infantile rites. The Sutherland source of distemper comes upon someone who had prayed at an altar-like rock formation and gone on to slog through the jet-black muck of the tidal flats. He pushes the latter’s face and the rest of his head into the wet, black substance in some kind of assertion of powers he doesn’t possess. With a grinding sound design becoming more insistent, One Eye has a premonition of a blood-soaked attack upon him. He tries to balance rocks in a column formation. Fails; and a bit later he tries again and succeeds—his way with craft calling to him as a significant stand. The chubby aggressor demands that they return; the leader vetoes that idea with, “We’ve raised the cross! Now we bring the sword!” One Eye looks on in silent contempt. In one disastrous outburst, the contrarian declares to the chief, “One Eye took us to hell. And there is no God!” He pulls out his dagger and lunges at the protagonist, who slashes his throat with his axe. The subsequent repeated chopping him to bits, blood splashing up, underlines One Eye’s realization that sustained harmony has no hope.

He strides away from his odious travelling companions and he stops to look back at the boy, who then follows him into the hills. Some stragglers try to follow them, including the leader’s careful son. During a pause from negotiating the high country, the latter regards the two strangers standing together. “What did he say?” he asks the boy. “We’re gonna die,” is the answer. “Then he’s lyin’!” the son insists. One Eye’s slight smile at this point contains no joy. The son turns back to join his father who has already been felled by many arrows. The boy sadly beholds the old theologian, a man of hope, who smiles at him. Then the protagonists reach the salt water of the estuary, and a numerous band of natives appears. One Eye gives the boy a little smile (their telepathy in fact having given solace on many occasions) and he touches his arm. He proceeds toward the locals who have their fun. Then, in vague recognition of the warrior’s integrity, they leave the boy unharmed, which is to say, to starve like the folks on the platforms. But unlike those folks, he’s seen something of the world and its promise, over and above its savagery.

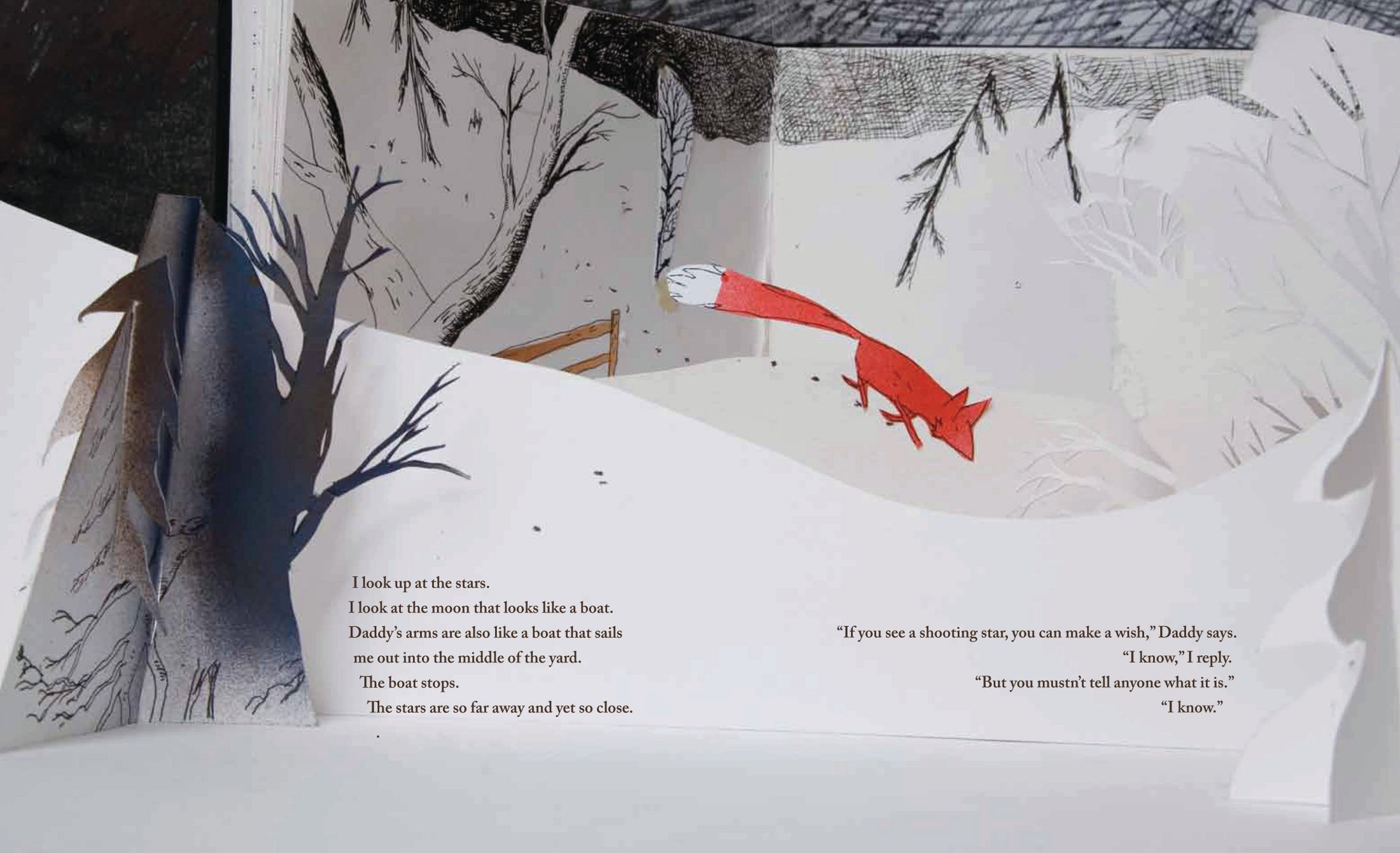

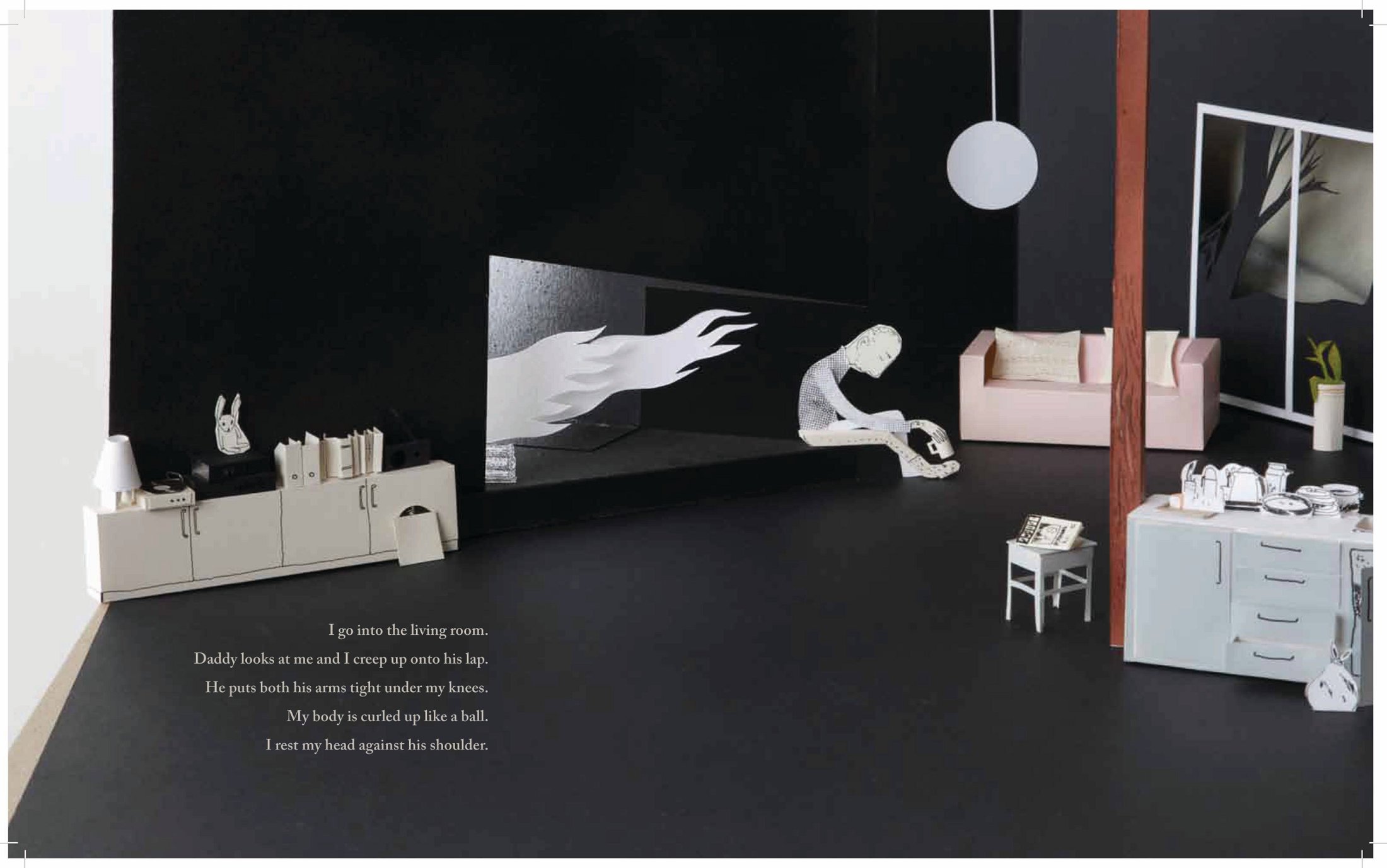

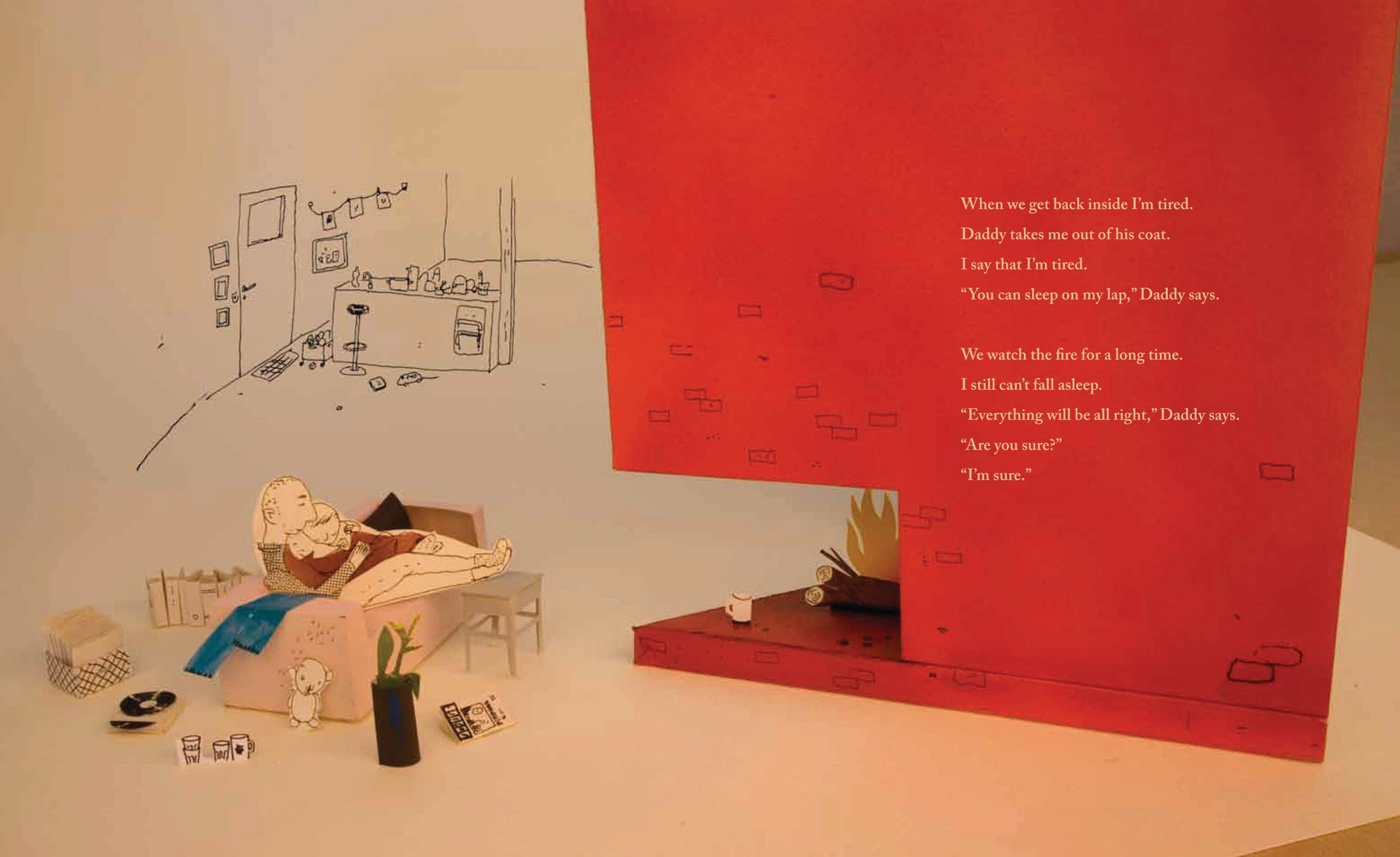

Incandescent picture book ‘My Father’s Arms Are A Boat’ from Norway

by Sam Juliano

There is something about the Scandinavian sensibility that seems to infuse their artistic output with a pervading sense of melancholy and darker themes. It is easy to understand when one considers the shorter days, colder climate and generally more austere and cerebral mind set (cliches to a degree, but this has always been the perception) and the tendency for their arts to reflect a more pensive and philosophical mood. One may immediately think of the brooding death-obsessed master filmmaker Ingmar Bergman, the playwright extraordinaire August Strindberg, who explored naturalistic tragedy, the iconic painter Edvard Munch, whose masterpiece The Scream, is a prime example of evocative treatment of psychological themes. Carl Theodor Dreyer, whose Vampyr, The Passion of Joan of Arc and Day of Wrath rank among the greatest of all films was another who examined state of mind in harrowing terms, and a long string of contemporary filmmakers like Thomas Vinterberg have relentlessly examined family strife and depression. In music there has always been a melancholic undercurrent in the nature-infused work of Jean Sibelius and Edvard Grieg.

Stein Erik Lunde and Oyvind Torseter’s sublime and incandescent picture book My Father’s Arms Are A Boat was recently named as a Batchelder honor book by the American Library Association in the one category that awards foreign language achievement, providing that it has been translated. The translation for My Father’s Arms Are A Boat is by Kari Dickson, and it is extraordinarily effective and deeply-felt. Starkly set during the dead of winter in and around an unforgiving country house lived in by a father and young son (“My window is pitch black. I have socks on, and a wooly sweater under my pajamas. I can’t sleep. It’s quieter now than it’s ever been.”) the story is poetically and suggestively told with a great deal of shivery emotion:

I go back into the living room.

Shubhajit Lahiri ties the knot

Our longtime friend and cinematic colleague Shubhajit Lahiri has happily announced that he and his lovely bride Riya were wed in a beautiful ceremony in India on January 21st. We at Wonders in the Dark were thrilled beyond words to hear of this surprising but most welcome news, and we wish this perfect couple the very best in the years ahead. So much seems to be coming together for the “king of the capsule” as of late and this ultimate final piece to the puzzle is one of supreme magnificence. Here’s to a life of love, success and eternal bliss! (click on ‘continued reading to see second photo)

Panel Discussion on books at Simmons College in Boston, Omar and The Complete Hitchcock Festival on Monday Morning Diary (February 24)

Sam with Horn Book editor-in-chief Roger Sutton after panel discussion at Simmons College in Boston on Thursday, Feb. 20.

by Sam Juliano

The past week’s spotlight event was staged on the fifth floor penthouse of the management building at Simmons College in Boston on The Fenway, just a stone’s throw away from the famed baseball stadium. Or maybe just a bit further than that. The 90 minute panel discussion “Why did that book win?” was moderated by longtime Horn Book editor-in-chief Roger Sutton. His co-panelists included executive editor Martha Parravano, Lesley University children’s literature professor Julie Roach and Kirkus Reviews book critic Vicky Smith, all of whom vigorously promoted a spirited discussion centering around the recent awards given out by the American Library Association. Ms. Roach expressed gleeful surprise that children’s author extraordinaire Kate Di Camillo’s profusely illustrated Flora & Ulysses won the Newbery Medal despite the general aversion to books that veer away from the generally all-prose format. A subsequent question from the audience later on addressed the confusion that sometimes emanates from the indecision of whether to honor words or pictures in a book that is seemingly divided equally, as was the case with the Caldecott Honor book Bill Peet: An Autobiography in 1990. Mr. Sutton pointed to a similar perception in 2008 when Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret won the Caldecott Medal despite the marked division of prose and pictures.

While Ms. Smith was delighted with Brian Floca’s Caldecott Medal triumph for Locomotive (“the author is no longer a bridesmaid”) there was some disappointment with some of the omissions, a sentiment that prompted Sutton to quip that the title of the discussion should have more in tune with “why certain book’s didn’t win?” Sutton bemoaned the failure of Kirkpatrick Hill’s Bo at Ballard Creek to achieve recognition in the awards process, while Ms. Perravano was amazed and disappointed that Cynthia Kadohata and Julia Kuo’s National Book Award winner The Thing About Luck didn’t figure in the final Newbery line-up. The panel addressed the matter of certain books that win the subsidiary awards (Pura Belpre, Coretta Scott King) but fail to win Caldecott or Newbery mention because the perception is that they have their own category. This has always been the mind-set of the Oscars, where a nomination or win in the animated film and/or foreign language category always always results in being passed over in the major categories. One spirited questioner talked about the specific perceptions and expectations of certain books aimed at a minority audience, and how those perceptions might be different among a more general reading audience. Another commenter, an artist and designer, appeared to intimate that some of the committee members should have a more artistic background, and that such a reform would result in different books winning the awards. This was not a position that others in the group (myself included) shared, and the panel and another commenter with an artistic background argued against such a narrow qualification.

With every panel member serving on past committees that have chosen Newbery, Caldecott, Sibert, and Pura Belpre winners, there was a long and intricate discussion of the painstaking ways books are studied and chosen, and how all members are sworn to secrecy as far as divulging specifics. Coffee and refreshments were offered to the nearly 100 people who showed up on a relatively mild evening in Beantown. Lucille, Danny and I had spend the afternoon in and around the Faneuil Hall marketplace, with Danny an enthusiastic visitor at Newbery Comics, an impressive book, DVD, blu ray and comic store off the outdoor strip. We ate in the Bell in Hand Tavern, which is touted as the “oldest tavern in the United States (1795)” and where we enjoyed burgers and eggplant fries. (Heck once in while we can manage that kind of food. Ha!). The nearly four hour ride home the same night (mostly rain-drenched) brought us to our door a little after midnight. All in all a memorable time was hat on this quick trip.

My meeting with Roger and a corresponding photo appeared here in The Horn Book:

http://www.hbook.com/2014/02/blogs/read-roger/book-win/

Lucille and I (Sammy for all the Hitchcocks) took in the Oscar-nominated OMAR on Saturday night in Montclair, and managed four films in The Complete Hitchcock Festival at the Film Forum. Three of the four films were seen in succession on Sunday.

Omar **** 1/2 (Saturday night) Bow Tie Cinemas

Blackmail *** 1/2 (Friday night) Hitchcock at Film Forum

The Lodger (1927) **** 1/2 (Sunday) Hitchcock at Film Forum

North by Northwest (1959) ***** (Sunday) Hitchcock at Film Forum

To Catch a Thief (1955) *** 1/2 (Sunday) Hitchcock at Film Forum

Young Sammy and I took on Hitchcock with veracity over the weekend, watching NORTH BY NORTHWEST, THE LODGER and TO CATCH A THIEF in succession on Sunday at the Film Forum. As always, the wildly implausible but wholly exhilarating NORTH BY NORTHWEST provided one of the most entertaining cinematic experiences ever, even being watched for the umteenth time. But this was Sammy’s first viewing of the 1959 classic, and to my extreme delight he talked about it all the way home–the Mount Rushmore climax, the crop duster sequence and the entire wrong man scenario. The color cinematography by Robert Burks is as ever astounding, and Bernard Herrmann’s music is magnificent. Oh yes, there’s the suave Cary Grant, one of the greatest of actors, and that sexy ambiguous blonde Eva Marie Saint and a superb James Mason in support. THE LODGER could well be Hitch’s greatest silent, and a viewing of the pristine BFI print on the big screen made me fall in love with this atmospheric work yet again. A moody film where sex rules over the identity of the murder, the film is tinged with German Expressionism and some eerie nightime scenes, and contains a great matinee turn by Ivor Novello.

The very best review I have ever read on THE LODGER was posted at ONLY THE CINEMA by the incomparable Ed Howard:

http://seul-le-cinema.blogspot.com/2012/05/lodger-story-of-london-fog.html

TO CATCH A THIEF is not one of Hitch’s strongest films, but in ways it is irresistible. The French Riviera is a great place to make a film, and cinematographer extraordinaire Robert is on top of his game again with some gorgeous lensing. Grant is on board again, as is a ravishing Grace Kelly.

The silent BLACKMAIL, about a rape and murder and some left behind evidence, was filmed at the same time as the talkie version, but the rich BFI restored print makes quite a case for its stand alone worth.

The Palestinian OMAR (directed by Hany Abu-Assad) is a tension-packed thriller about trust and betrayal, with a romantic sub-plot. Actually, one of the film’s creators said this week it is more a love story than a political one. It is wholly riveting, and was nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

I have re-posted last week’s links with a few revisions:

At Tuesdays with Laurie, the indomitable Ms. Buchanan offers up another provocative post: http://tuesdayswithlaurie.com/2014/02/18/under-over-through/

Head over to FilmsNoir.net pronto to check out Tony d’Ambra’s fantastic Top 25 film noirs in a tremendous post: http://filmsnoir.net/film_noir/filmsnoir-nets-top-25-films-noir.html

At Noirish the exceedingly gifted and prolific author John Grant has posted a splendid takedown of 1962′s little-seen “Stark Fear”: http://noirencyclopedia.wordpress.com/2014/02/23/stark-fear-1962/

Stephen Mullen (Weeping Sam) has declared “Inside Llewyn Davis” as the best film of 2013 and one of the Coens’ most formidable works at The Listening Ear: http://listeningear.blogspot.com/2014/02/inside-llewyn-davis.html

Dean Treadway continues his fabulous annual cinematic coverage with an in-depth look at 1927 at Filmacability: http://filmicability.blogspot.com/2014/02/1927-year-in-review.html

Judy Geater has launched her new series on Douglas Sirk at Movie Classics with a terrific essays on “Has Anybody Seen My Gal?”: http://movieclassics.wordpress.com/2014/02/16/has-anybody-seen-my-gal-douglas-sirk-1952/

John Greco has written a superb review of Luchino Visconti’s extraordinary “Bellissima” at Twenty Four Frames: http://twentyfourframes.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/belissima-1952-visconti-luchino/

At Scribbles and Ramblings Sachin Gandhi has the South American Movie World Cup pairings up for your perusal: http://likhna.blogspot.com/2014/01/south-american-films.html

At Overlook’s Corridor Jaimie Grijalba is up to “screenplays” in the continuing examination of his annual ‘Frank Awards’ given to the best films and components: http://overlookhotelfilm.wordpress.com/2014/02/14/frank-awards-2013-screenplays/

Pat Perry’s latest post at Doodad Kind of Town superbly addresses “Philomena” and “Inside Llewyn Davis”: http://doodadkindoftown.blogspot.com/2014/01/surprise-surprise.html

At Dee Dee’s ‘Ning’ network site she has posted some spectacular and rare Hitchcock posters in honor of the Film Forum’s great Festival on the prolific icon: http://filmnoire.ning.com/forum/topics/darkness-before-dawn-takes-a-peek-at-foreign-posters-and

Jon Warner has posted a fantastic essay on the documentary masterwork “The Act of Killing” at Films Worth Watching: http://filmsworthwatching.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-act-of-killing-2012-directed-by.html

At FilmsNoir.net Allan Fassions has written a superb essay on 1955′s “Dementia” for the site’s erstwhile proprietor Tony d’Ambra: http://filmsnoir.net/film_noir/alan-fassioms-on-dementia-1955-beatnik-noir.html

And speaking of Fassions, his site is now the latest inclusion on the WitD sidebar. It is called “Stranger on the 3rd Floor” and it looks like a fabulous place to visit: http://strangeronthe3rdfloor.wordpress.com/

At The Last Lullaby filmmaker Jeffrey Goodman is leading up with his 12 Best Films of 2013: http://cahierspositif.blogspot.com/2014/01/my-top-twelve-films-of-2013.html

The great Canadian artist Terrill Welch is leading up at her sublime Creativepotager’s blog with a post titled “One Brush Stroke After Another”: http://creativepotager.wordpress.com/2014/02/10/one-brushstroke-after-another/

As ever, Samuel Wilson is posting superb reviews that may have esaped the radar. His latest great piece to that end at Mondo 70 is an essay on “Greed in the Sun”: http://mondo70.blogspot.com/2014/02/greed-inthe-sun-cent-mille-dollars-au.html

Patricia Hamilton has written a tremendous book review on Anish Majumdar’s “The Isolation Door” at Patricia’s Wisdom, and the author chimed in: http://patriciaswisdom.com/2014/02/the-isolation-door-a-novel-anish-majumdar/

Shubhajit Lahiri has penned a provocative capsule on the Argentinian film “Wake Up Love” at Cinemascope: http://cliched-monologues.blogspot.com/2014/02/wake-up-love-despabilate-amor-1996.html

David Schleicher has penned a fabulous review of the Iranian “The Past” at The Schleicher Spin: http://theschleicherspin.com/2014/02/09/secrets-and-lies-in-the-past/

Brandie Ashe has posted a wonderful post on Shirley Temple at True Classics: http://trueclassics.net/2014/02/11/remembering-shirley-temple/

Mike Norton has penned some superlative pieces on Hip Hop at Enter the Screen: http://enterthescreen.wordpress.com/

Joel Bocko posts about the screen-capping he’s managed over the past year at The Dancing Image: http://thedancingimage.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-final-watchlistscreencap-some-notes.html

Roderick Heath brings unprecedented scholarship to Ivan Reitman’s “Ghostbusters” at Ferdy-on-Films: http://www.ferdyonfilms.com/2014/ghostbusters-1984/21071/

J.D. LaFrance leads up with a terrific review on “Neuromancer” at Radiator Heaven: http://rheaven.blogspot.com/2014/02/neuromancer.html

Drew McIntosh has again offered up a fascinating post at The Blue Vial, showcasing works by Walerian Borowczyk and David Lynch: http://thebluevial.blogspot.com/2014/01/end-of-road.html

Sachin Gandhi reports on ‘Sundance Film Festival’

by Sachin Gandhi

2014 marked the 30th anniversary of the Sundance Film Festival, a festival that has been the launching pad for many exciting cinematic voices over the years. The festival’s importance in discovering new directors was nicely highlighted by the trailer shown before all the films which gave a glimpse of some of the stellar titles that played at the festival. The first Sundance was held in 1985 but it is acknowledged that the festival shot into the limelight in 1989 with Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotapes which changed the perception of the festival. Besides being the launching pad for Soderbergh, Sundance ushered the discovery of many other American directors including Quentin Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, 1992), Kevin Smith (Clerks, 1994), Kelly Reichardt (River of Grass, 1994), Paul Thomas Anderson (Hard Eight, 1996) and Darren Aronofsky (Pi, 1998). All of these directors, plus many more, have made the jump from Independent to Commercial cinema thanks to their discovery at Sundance. Even James Wan’s Saw premiered at Sundance before it transformed into a multiplex franchise.